Beyond Light: New Frontiers in the Oldest Science - Part 1

Part 1: Particles

By Dylan L. Jow

For millennia, astronomy has been the study of light. Throughout most of its long history, astronomers relied solely on light from the stars that they could see with their own eyes. That changed in the 17th century when the telescope was invented, allowing astronomers to see distant objects, including other galaxies that were too dim for the naked eye to see.

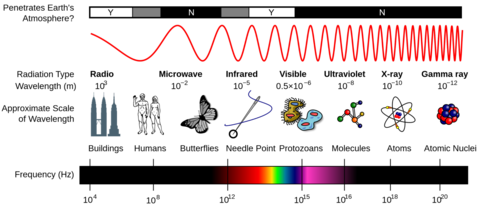

In the 20th century, new technologies unlocked our ability to see light beyond the visible spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays (see Fig. 1, below). Now the 21st century stands to be the century in which astronomy pushes beyond the confines of light and begins to detect new signals such as neutrinos, cosmic rays, and gravitational waves. In this two-part blog post, we will explore this new era of “multi-messenger astronomy,” which refers to the practice of combining information from these different cosmic messengers to learn more about the universe than with light alone. Work conducted at KIPAC on neutrinos and cosmic rays is advancing this paradigm-altering frontier. Stay tuned for the next post in two weeks about KIPAC’s progress on gravitational waves!

Cosmic Rays

Photons — particles of light — are by far the most accessible particles emitted by stars and other celestial bodies. Lightweight and fast moving, a photon is difficult to stop once it's created. A photon emitted by the cosmic microwave background can travel billions of lightyears before stopping. Yet some are fortunate enough to land in our telescopes.

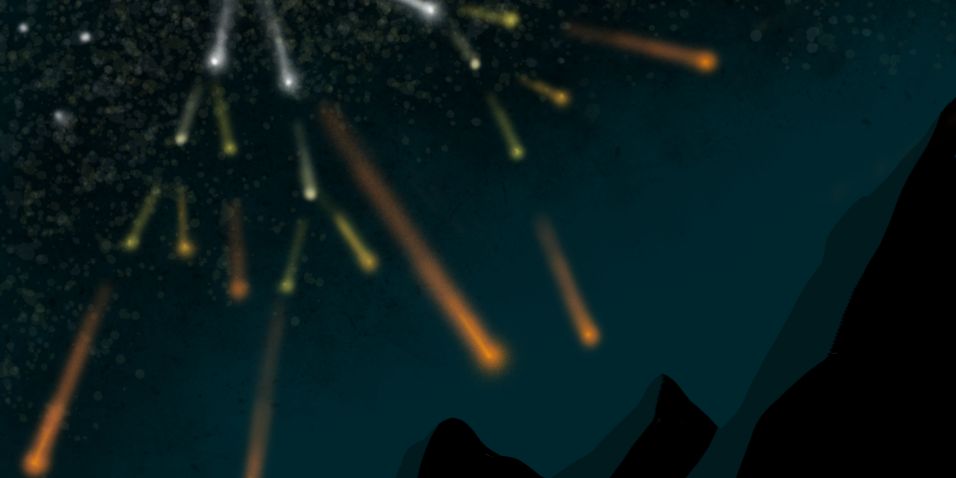

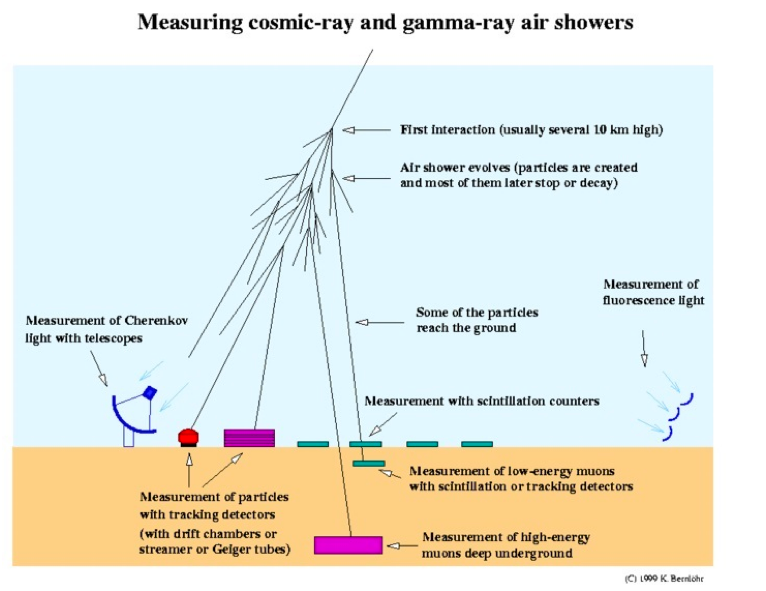

But photons are not the only particles produced by stars and other celestial phenomena. “Cosmic ray” is an umbrella term for the particles of normal matter (think protons, electrons, and atomic nuclei) emitted with high enough energies to reach Earth across the vast expanses of space. We detect cosmic rays because they produce a cascade of particles when interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere that we observe with ground-based detectors (see Fig. 2).

Cosmic rays were discovered by Victor Hess in the early 20th century, but using them to learn about astrophysics has remained challenging. One challenge is that cosmic rays do not travel in straight lines, but are scattered by magnetic fields many times on their journey to Earth, often fully reversing direction. Tracing the origins of these mysterious high-energy particles remains a major outstanding question in astronomy. Theoretical work by Noemie Globus and Iryna Butsky at KIPAC is making progress towards resolving this “cosmic ray transport” problem. By solving this problem, we will better be able to understand the major role cosmic rays are thought to play in the evolution of galaxies and star formation. My own work has also brought me into contact with cosmic rays. We recently proposed that cosmic ray scattering is related to the mysterious Extreme Scattering Events that radio sources are sometimes observed to undergo.

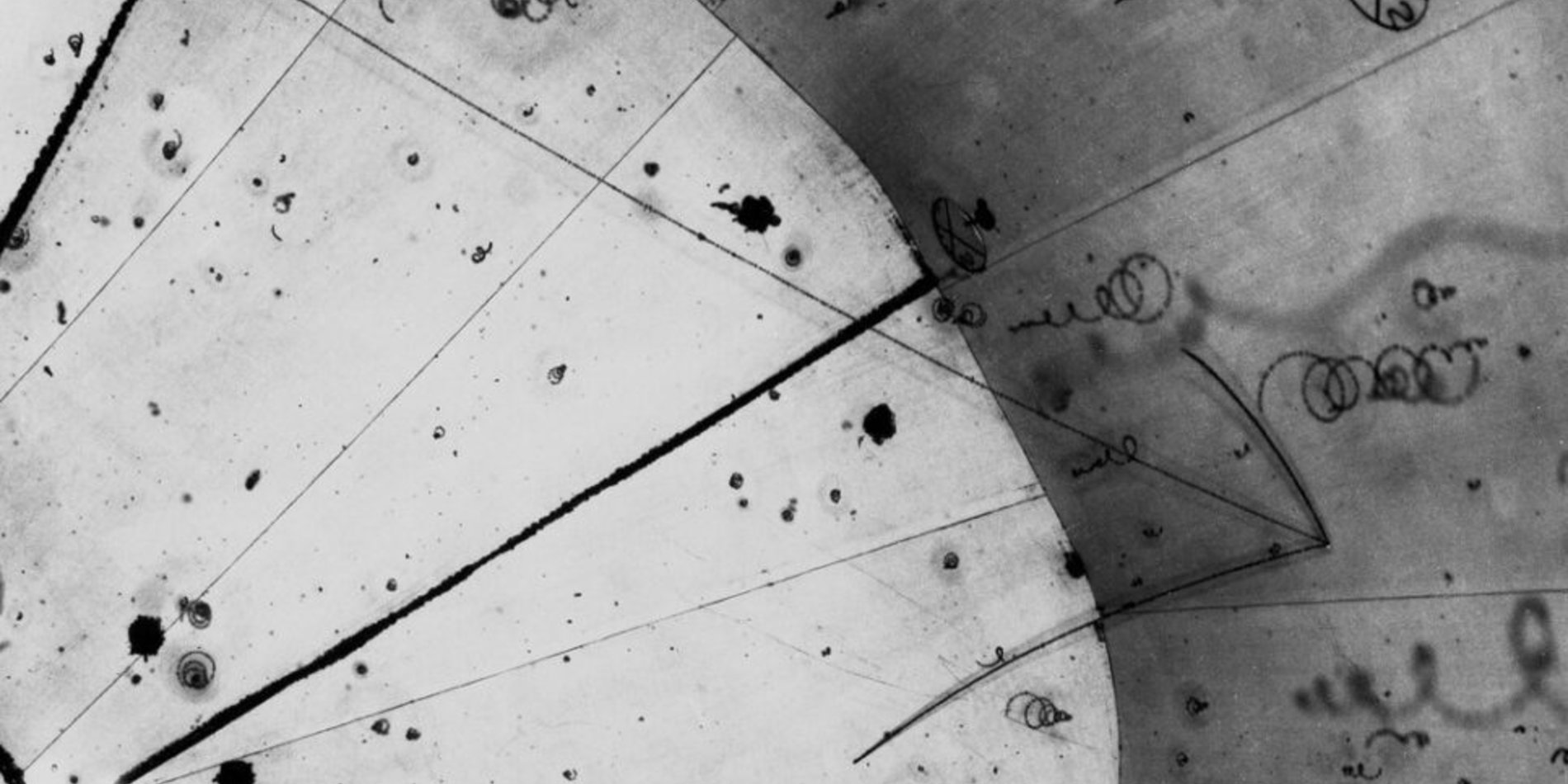

Ionized gas in the Milky Way Interstellar Medium sometimes acts like a magnifying glass, causing radio sources to undergo large changes in brightness. The magnifying structures in the medium are thought to be thin sheets of gas sustained by magnetic fields, which in turn may be the very magnetic fields responsible for cosmic ray scattering. By untangling the way cosmic rays move through our galaxy, we may also resolve a long-standing mystery in radio astronomy.

Neutrinos

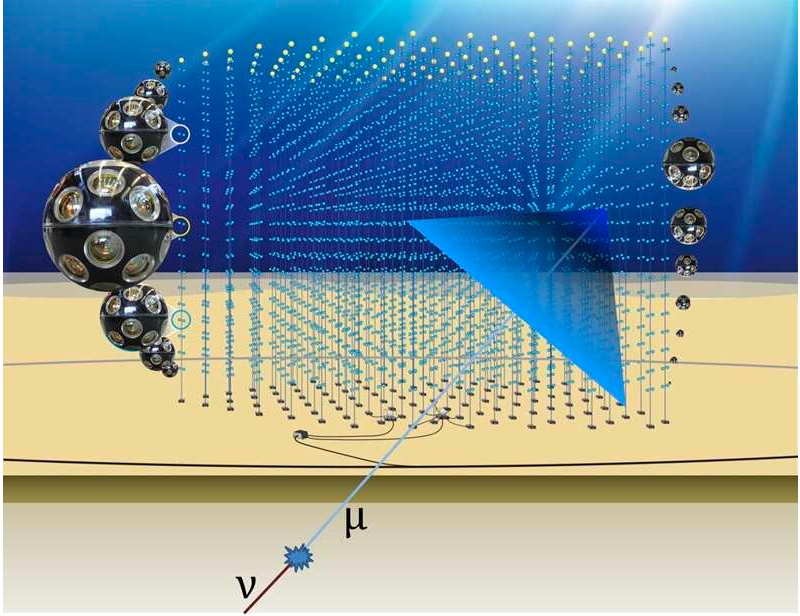

Neutrinos are another particle produced in abundance by the heavens. Our sun emits 1038 neutrinos per second. But if a photon is difficult to stop once it gets going, a neutrino is next to impossible. It takes a lightyear-long block of lead to stop any given neutrino, which means that detectors on Earth should have no hope of capturing the vast majority of neutrinos that pass through them. Instead, modern neutrino observatories, like KM3Net and IceCube, use highly-sensitive optical sensors to detect the Cherenkov light that is emitted when a neutrino interacts with water (see Fig. 3). By placing many such detectors in large volumes of (sometimes frozen) water, neutrino observatories can catch the rare occasion when a neutrino interacts with the water. For roughly every quadrillion neutrinos that pass through the KM3Net detector, only one will trigger a detection. Neutrino science sits at the intersection of fundamental particle physics and astrophysics, allowing us to use space as a laboratory to test some of the most fundamental laws of nature that would be difficult to test in a lab.

The Era of Multi-messenger Astronomy

One of the broad goals of astrophysics is to be able to describe, in detail, the physical processes that produce the celestial bodies that we observe. We want to answer questions like: what are the physical processes that cause supernovae? What is the physical composition of a neutron star? What mechanisms trigger the radio emission that we observe as pulsars? Combining different observables from multiple cosmic messengers (like photons, cosmic rays, and neutrinos) will be a key tool for answering these questions. By tracing the different particles emitted by the same astrophysical phenomenon, we can learn about the environments in which these particles were created. In the coming decades, multi-messenger astronomy will be a powerful tool that astronomers can leverage to deepen our understanding of the sky. The particles discussed here, however, are not the only sources of information that we can detect on earth. In the next part, we will discuss mysterious ripples in space-time: gravitational waves.

Read more

- On the cusp of cusps: a universal model for extreme scattering events in the ISM

- A Unified Model of Cosmic Ray Propagation and Radio Extreme Scattering Events from Intermittent Interstellar Structures

Edited by Jack Dinsmore, Lori Ann White, and Xinnan Du

Related Research Areas

Extreme Astrophysics

We at KIPAC have an active Compact Object Group Meeting (COG) which meets Tuesdays to discuss progress in extreme astrophysics.

Physics of the Universe

At KIPAC, we are working to understand the physics that shapes the origins, evolution and fate of the Universe.Related People

-

Physical Science Research Scientist

Physical Science Research Scientist -

Postdoctoral Scholar

Postdoctoral Scholar