Beyond Light: New Frontiers in the Oldest Science - Part 2

Part 2: Waves

By Dylan L. Jow

In the last post, we talked about how astronomers are pushing our frontiers of knowledge by using new technologies to detect particles other than light emitted by celestial objects. However, the story doesn’t end with cosmic rays and neutrinos.

Gravitational Waves

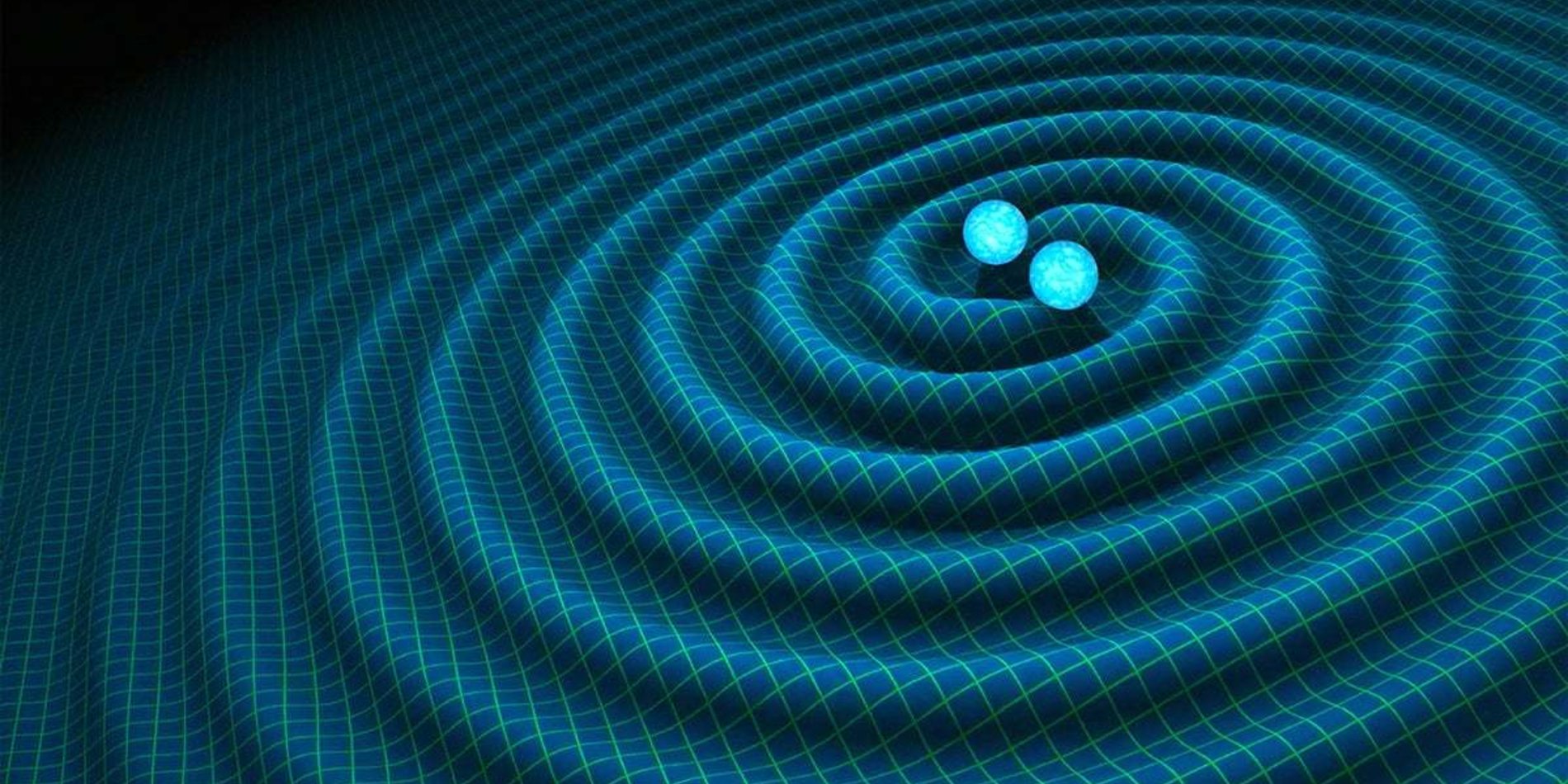

Gravitational waves represent perhaps the most peculiar frontier beyond light. Unlike cosmic rays and neutrinos, which are particles of ordinary matter, gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of spacetime itself. They’re produced by cataclysmic events, such as two black holes or neutron stars colliding. These objects are so heavy that they send out waves in spacetime as they circle each other.

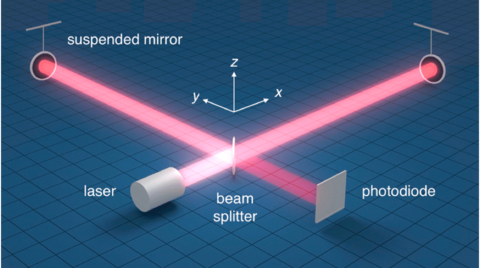

Gravitational waves are not measured by collecting particles in a detector, but by measuring the warping of space itself as a wave passes. On Earth, lasers are used to measure these minute changes in distance between two points in systems known as interferometers (see Fig. 1). In 2015, the first gravitational wave was detected, confirming a key prediction of Einstein’s theory of relativity and heralding a new era of gravitational wave astronomy. Since then, dozens of gravitational waves have been detected by the LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA interferometers. By detecting these ripples caused by merging compact objects, we have been building up a census of the population of black holes in the Universe over the last decade. Scientists at KIPAC have been instrumental in building the technologies that have enabled LIGO and will continue to enable its scientific goals.

But the gravitational waves detected by interferometers on Earth are produced by stellar mass compact objects (black holes and neutron stars that have similar masses to stars). Super massive black holes (which can have masses up to a billion times that of the sun) also produce gravitational waves as they merge. These leviathans produce gravitational waves with wavelengths that can span the distance between the sun and the nearest stars. Such enormous wavelengths can’t be detected on Earth, so we need to get clever. Enter pulsar timing arrays.

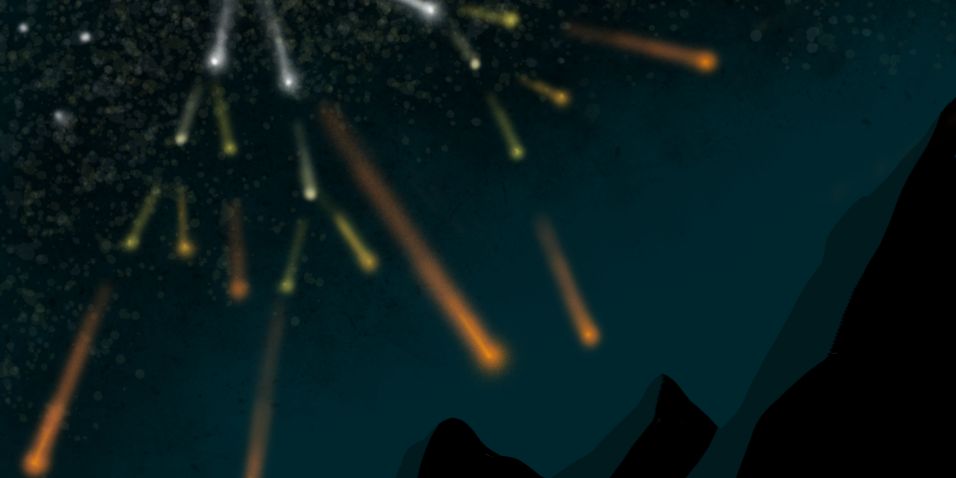

Pulsars are rapidly rotating neutron stars that emit pulses of radio light at a fixed rate. Because of the regularity of their bursts, we can use them like clocks. By measuring the subtle differences in the rate of each clock over time, we can tell that a gravitational wave is passing by. By utilizing many of these pulsar-clocks scattered throughout the galaxy, we can create a pulsar timing array, turning the Milky Way into one enormous telescope (see Fig. 2). In 2023, several independent collaborations used pulsar timing arrays to obtain concrete evidence of the existence of a background hum of ultra-long wavelength gravitational waves (Scientists find key evidence for existence of nanohertz gravitational waves).

While this detection was a huge success, we have a long way to go before our pulsar timing arrays are sensitive enough to isolate individual waves from individual merging black holes. That doesn’t stop theorists like me from thinking ahead to what science we can do once we reach that milestone. Recently, we published a short letter demonstrating that we can use isolated individual gravitational waves to make exquisitely precise measurements of the expansion rate of the Universe, far beyond what has been achieved thus far using light.

But the holy grail of pulsar timing arrays would be the detection of a cosmic gravitational wave background. The more familiar cosmic microwave background is sometimes called the “baby picture of the Universe”, emitted when the Universe was only 100,000 years old. Before that, the Universe was too hot and dense for light to travel very far. As a result, it’s impossible for us to see the Universe at any earlier time with light alone. Gravitational waves, however, don’t care how hot or dense the Universe is—they just sail right through. If we can detect a cosmic gravitational wave background with pulsar timing arrays, we will have captured the “fetal ultrasound of the Universe.”

Conclusion

Astronomers face unique challenges as scientists because we can’t make whole universes in the lab to run experiments and test hypotheses. We only get the one Universe, and we only get to see it from one viewpoint: Earth. The history of astronomy can essentially be understood as a long process of finding new ways of collecting information from the limited amount of light that happens to make its way to us from the outer reaches of the cosmos. Now we are beginning to learn about the cosmos through materials other than light: cosmic rays, neutrinos, and mysterious gravitational waves. The ongoing effort to realize this dramatic shift in the history of astronomy has required not only the technological expertise of instrumentalists and observers, but also bold, new ideas from theorists for how to leverage these new observables for deeper insights into the Universe. Photons will always be the work-horse of astronomy, but with these probes in our toolbox, a new Universe of questions await.

Edited by Jack Dinsmore, Lori Ann White, and Xinnan Du

Related Research Areas

Extreme Astrophysics

We at KIPAC have an active Compact Object Group Meeting (COG) which meets Tuesdays to discuss progress in extreme astrophysics.

Physics of the Universe

At KIPAC, we are working to understand the physics that shapes the origins, evolution and fate of the Universe.Related People

-

Postdoctoral Scholar

Postdoctoral Scholar