Nature’s Ultimate Particle Accelerators

Cosmic rays are everywhere

Right now, unless you are a hundred feet underground, a few relativistic particles are passing through your head every second. They go right through the atmosphere, the clouds, the roof, the ceiling, and anything else you might try to shield yourself with, at nearly the speed of light. These relativistic particles—muons, to be specific—are the subatomic shards of higher-energy nuclei, which we call cosmic rays. They strike the atmosphere and mostly don’t harm you because the Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field protect you.

Most cosmic rays have about a GeV of energy, something that the SLAC Linear Accelerator can produce, but once every few seconds, an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray with 100 billion GeV will hit Earth’s atmosphere. That’s more than ten million times more energy than humanity’s best particle accelerator, CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, can achieve. And scientists still don’t know how nature does that!

The mystery of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays

Over the last century of research into cosmic rays, scientists have thought of many possible sources of cosmic rays, but the task is complicated by magnetic fields throughout the Universe that scatter the particles and randomize their arrival direction. We’ve known for a few decades that these ultra-high-energy ones can’t come from within our galaxy because galactic magnetic fields are not strong enough to fully randomize the arrival directions of cosmic rays over distances to anything within our own galaxy, but the sources still appear to be randomized relative to sources farther away.

Scientists have proposed supermassive black holes, the powerful jets emerging from those black holes, gamma-ray bursts, merging neutron stars, magnetars, and decaying dark matter, just to name a few candidates. The range of ideas hints at the challenge of finding some source in the Universe that can accelerate particles to these extreme energies, as much kinetic energy as a major league fastball but concentrated in a single atomic nucleus.

Reviving old ideas with new recipes

Our recent paper revisits and updates a model that has been underappreciated for the past 30 years because scientists incorrectly believed that these cosmic rays were all protons. Now that most people in the field think that they include heavy nuclei, we are revisiting the idea that these extreme cosmic rays come not from the usual suspects but from some of the largest and oldest structures in the Universe: accretion shocks around the cosmic web.

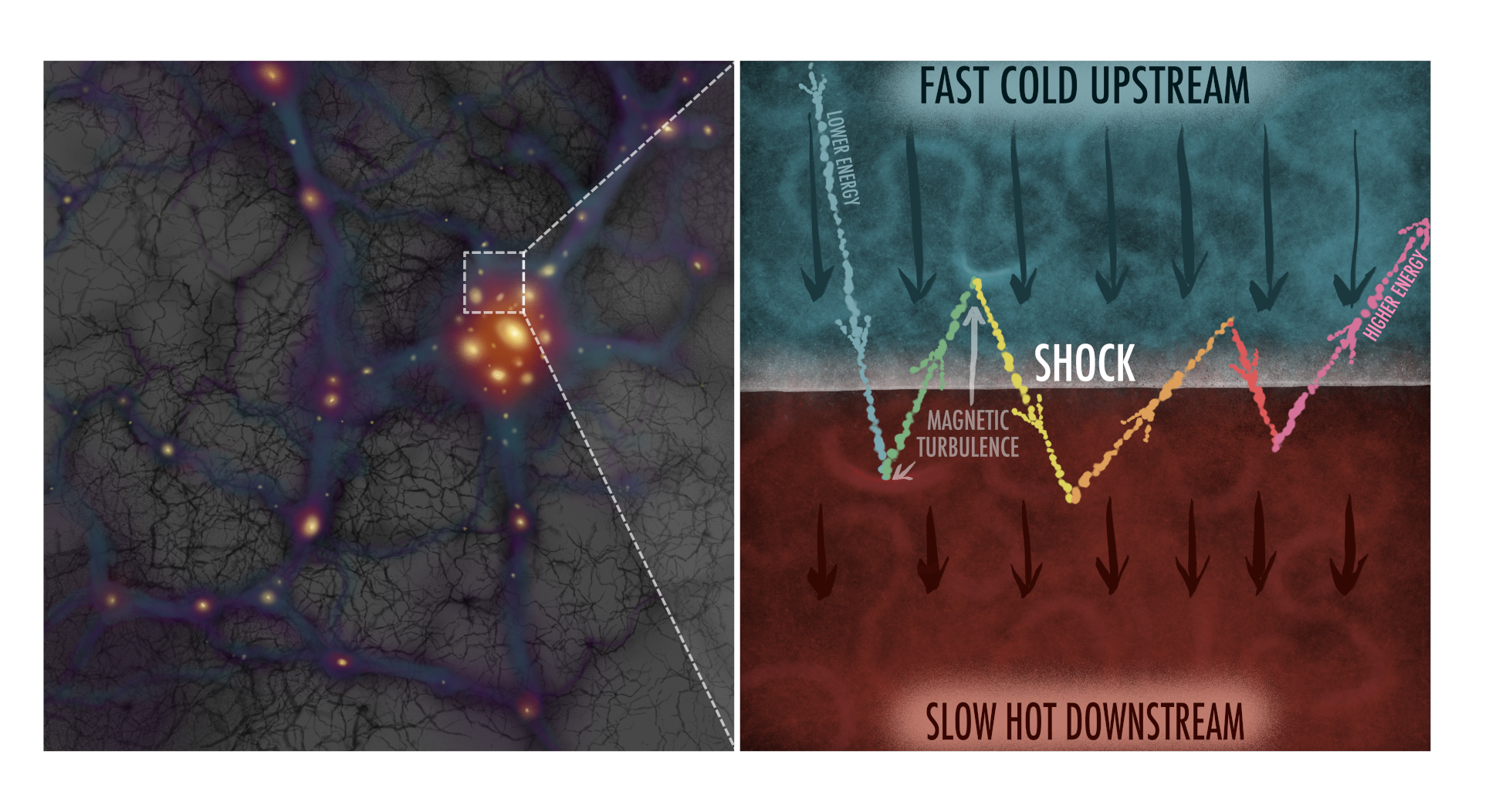

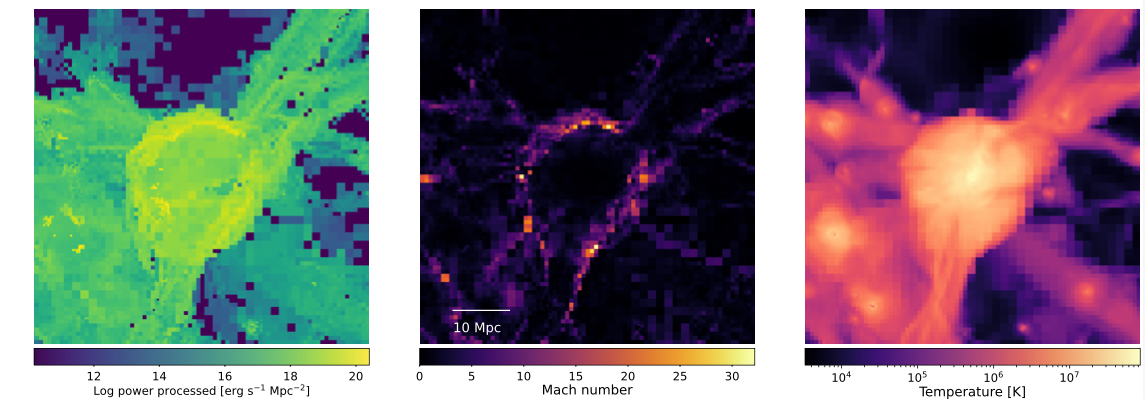

Accretion shocks form when gravity pulls galaxies, gas, and dark matter into what is known as the large-scale structure of the Universe, a network of clusters of tens to thousands of galaxies connected by filaments of more galaxies and matter. This cosmic web has been building up over the entire history of the Universe as overdense regions attract even more matter from underdense regions. As low-density gas from cosmic voids continuously falls onto the clusters and filaments with supersonic speed, it inevitably forms strong and stable shock fronts all around this structure. These accretion shocks are older than 8 billion years and are dozens of times wider than the Milky Way Galaxy, making them the oldest and largest shocks in the Universe. So, they are good candidates to accelerate the most extreme cosmic rays through a process called diffusive shock acceleration, in which particles scatter back and forth across a shock front and gradually gain energy by tapping into the bulk motion of the plasma. See Figure 1 for a schematic drawing of this process. Smaller shocks within the Milky Way are nearly certain to explain the origin of most galactic cosmic rays via diffusive shock acceleration, making these enormous accretion shocks natural candidates to accelerate the most extreme cosmic rays as well. See Figure 2 for a simulation of accretion shocks forming.

We updated the model of accretion shocks to include effects from many different advances in astrophysics over the past 30 years: knowledge of how these shocks formed at least 8 billion years ago, how plasma instabilities and turbulent dynamos (plasma processes that amplify magnetic fields) amplify the magnetic field over billions of years, how the extreme cosmic rays appear to be at least partially iron, and the role of the intermediate-sized shocks around filaments as a step in a hierarchy of acceleration between Galactic cosmic rays and the extreme cosmic rays from cluster shocks. Altogether, these modifications of the model make it more attractive in many ways. The most attractive part of the story to us is that it relies on the same general process—diffusive shock acceleration—in a hierarchy of shocks that build up the whole cosmic-ray spectrum through successive stages of acceleration. Other models require less well-known processes or environments, and they require more fine-tuning to give the relatively smooth spectrum that we observe.

So what’s the catch? We haven’t observed these accretion shocks well enough to know how strong they are and how high the magnetic fields are. And many astrophysicists think that these shocks don’t have magnetic fields strong enough for the job, so they stick with the more popular models invoking more point-like sources.

Upcoming multi-messenger observations (see this previous research highlight on multi-messenger astronomy), incorporating data from radio, optical, X-ray, gamma-ray, neutrino, gravitational wave, and cosmic rays, will narrow the possibilities for the source of extreme cosmic rays. Better radio observations of these accretion shocks will come from the Deep Synoptic Array in Nevada, revealing the presence of amplified magnetic fields. More precise measurements of the composition of cosmic rays from the Pierre Auger Observatory in Argentina will constrain models by their ability to produce cosmic rays of a given composition and energy. For now, our goal is to sharpen the model’s predictions so that observations can meaningfully test this picture and, in doing so, help narrow one of the longest-standing mysteries in high-energy astrophysics.

Edited by Jack Dinsmore, Xinnan Du, Sanskriti Das, and Lori Ann White

Related Research Areas

Extreme Astrophysics

We at KIPAC have an active Compact Object Group Meeting (COG) which meets Tuesdays to discuss progress in extreme astrophysics.

Physics of the Universe

At KIPAC, we are working to understand the physics that shapes the origins, evolution and fate of the Universe.Related People