How to precisely weigh a quasar’s host galaxy

A team of researchers from the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Lausanne, Switzerland, have found a way to use the phenomenon of strong gravitational lensing to determine with precision—about three times greater precision than any other technique—the mass of a galaxy containing a quasar, as well as its evolution in cosmic time. Knowing the mass of quasar host galaxies provides insight into the evolution of galaxies in the early Universe, useful for building scenarios of galaxy formation and black hole development. The results were published in Nature Astronomy.

“The masses of host galaxies have been measured in the past, but thanks to gravitational lensing, this is the first time that the measurement is so precise in the distant Universe,” explains Martin Millon, lead author of the study and currently a member of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics (KIPAC) at Stanford University. Millon and several KIPAC colleagues will continue to search for lensing quasars during his time at Stanford.

Combining gravitational lensing and quasars

A quasar is a luminous manifestation of a supermassive black hole that accretes surrounding matter, sitting at the center of a host galaxy. It is generally difficult to measure how heavy a quasar’s host galaxy is because quasars are very distant objects, and also because they are so bright that they outshine anything in the vicinity, making an estimate of the number and type of stars in the host galaxy based on its brightness impossible.

However, gravitational lensing allows us to compute the mass of the lensing object. Thanks to Einstein’s theory of gravitation, we know how massive objects in the foreground of the night sky—the gravitational lens—can bend light coming from background objects. A perfectly placed lens results in a strange ring of light—an Einstein ring—that traces an outline around the foreground lens and is actually a distortion of the background object’s light by the gravitational lens itself.

A decade ago EPFL astrophysicist Frédéric Courbin, senior author of the study, realized that he could combine quasars and gravitational lensing to measure the mass of a quasar’s host galaxy. For this, he had to find a quasar in a galaxy that also acts as a gravitational lens.

Only a handful of gravitational lensing quasars observed thus far

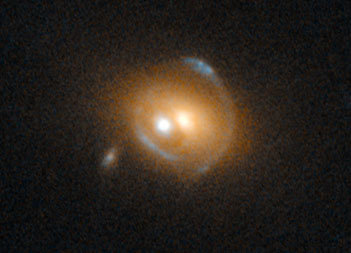

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) database was a great place to search for gravitational lensing quasars candidates, but to be sure, Courbin had to see the lensing rings. In 2010, he and colleagues commissioned time on the Hubble Space Telescope to observe four candidates, of which three showed lensing. Of the three, one stood out due to its characteristic gravitational lensing rings: SDSS J0919+2720.

The HST image of SDSS J0919+2720 shows two bright objects in the foreground that each act as a gravitational lens, “probably two galaxies in the process of merging,” explains Courbin. The one on the left is a bright quasar, within a host galaxy too dim to be observed. The bright object on the right is another galaxy, the main gravitational lens. A faint object on the far left is a companion galaxy. The characteristic rings are deformed light coming from a background galaxy.

Computational lens modeling to the rescue

By carefully analyzing the gravitationally lensed rings in SDSS J0919+2720, it is possible to determine the mass of the two bright objects…in principle. Disentangling the masses of the various objects would have been impossible without the recent development of a wavelet-based lens modeling technique by co-author Aymeric Galan, currently at the Technical University of Münich (TUM).

“One of the biggest challenges in astrophysics is to understand how a supermassive black hole forms,” explains Galan. “Knowing its mass, how it compares to its host galaxy and how it evolves through cosmic times, are what allows us to discard or validate certain formation theories.”

“In the local Universe, we observe that the most massive galaxies also host the most massive black holes at their centers. This could suggest that the growth of galaxies is regulated by the amount of energy radiated by their central black holes and injected into the galaxy. However, to test this theory, we still need to study these interactions not only locally but also in the distant Universe,” explains Millon.

Gravitational lensing events are very rare, with one galaxy in a thousand displaying the phenomenon. Since quasars are seen in about one of every thousand galaxies a quasar acting as a lens is a one-in-a-million phenomenon. The scientists expect to detect hundreds of these lensing quasars with the ESA-NASA mission Euclid, to be launched this summer with a Falcon-9 SpaceX rocket.

This article is adapted from a press release furnished by EPFL. For more information, see the original here.