Determining the Hubble-Lemaitre parameter with the Simons Observatory

by Giuseppe Puglisi

Cosmological research is one of the most mind-blowing areas of modern-day scientific research for several reasons, beginning with the tremendous strides that have been made in the last few decades, resulting in a picture that we now believe we understand quite well all the way back to nearly 14 billion years ago. The model that currently best describes evolution and structure of the Universe is referred to as Lambda-CDM or "LCDM" and is consistently in agreement qualitatively and quantitatively with virtually all observations we make. And with the enormous increase in the amount of data coming from different cosmic probes (for example, from Type Ia supernovae, galaxy surveys, gravitational lensing, the cosmic microwave background [CMB], and so on), our ability to extensively cross-check results and improve our theoretical understanding is only growing steadily.

But LCDM doesn't have absolutely perfect consistency currently, and when multiple independent measurements of the same parameter are involved, we have in fact been finding that some of the results are in tension with each other—the measurements don’t match up, even when error bars are taken into account. This could be a sign that the model is showing cracks that could enable us to gain insight into the ultimate nature of dark matter and dark energy, two of the most mysterious components of our LCDM picture.

Cracks in the model, Part I: Using SNIa as our probe

One of the most interesting and long-standing examples of a current tension is in measurements of the expansion rate of the Universe, usually referred to as the Hubble Constant, H0 (pronounced “H-nought,” which is the value of the Hubble-Lemaitre-Slipher parameter evaluated at the current time). There are several ways to infer the value of H0: one way is by means of what we call “standard candles,” distant sources of light whose absolute intensities are quite well known and calibrated. The classic cosmological example of this is a Type Ia Supernova (SNIa), commonly referred as a late Universe probe, because we observe them in (relatively) late times as compared to when the Big Bang happened, 13.7 billion years ago. Measurements from SNIa over the last few years have been yielding a value for H0 on the high side when compared to other measurements. For example, an analysis from Riess et al., (Jan 2018) quoted an H0 value of 73.48 +/- 1.66 km/ s/Mpc). However, other methods have yielded a significantly lower H0, as we will see.

Cracks in the Model, Part II: Using the oldest light in the Universe as our probe

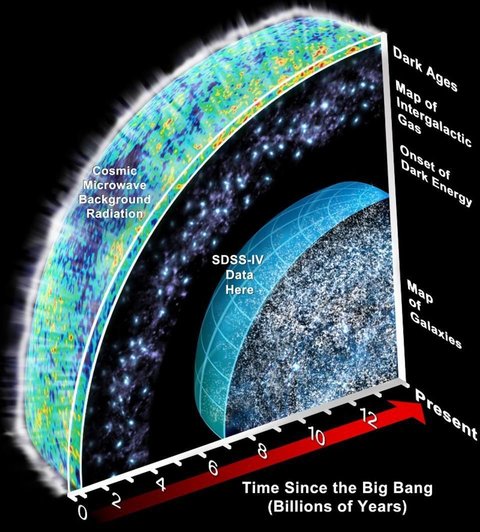

A completely different way of extracting H0 is to exploit “standard rulers”; in other words, objects whose geometric size can be precisely predicted from theoretical models.

To explain one version of this, let’s step back to about 370 to 380 million years after the Big Bang, when regular matter existed as a high-energy soup of ions that kept photons trapped within it, bouncing from one particle to the next. Cosmologists describe this situation as light being “coupled” to matter.

However, those hot particles of matter were cooling, and when they got cool enough to combine into neutral atoms, the photons could escape. This is called the “decoupling era.” The escaped photons make up the CMB, the oldest light in the Universe. (For more about the CMB see the April 2017 KIPAC blogpost by alum Kyle Story).

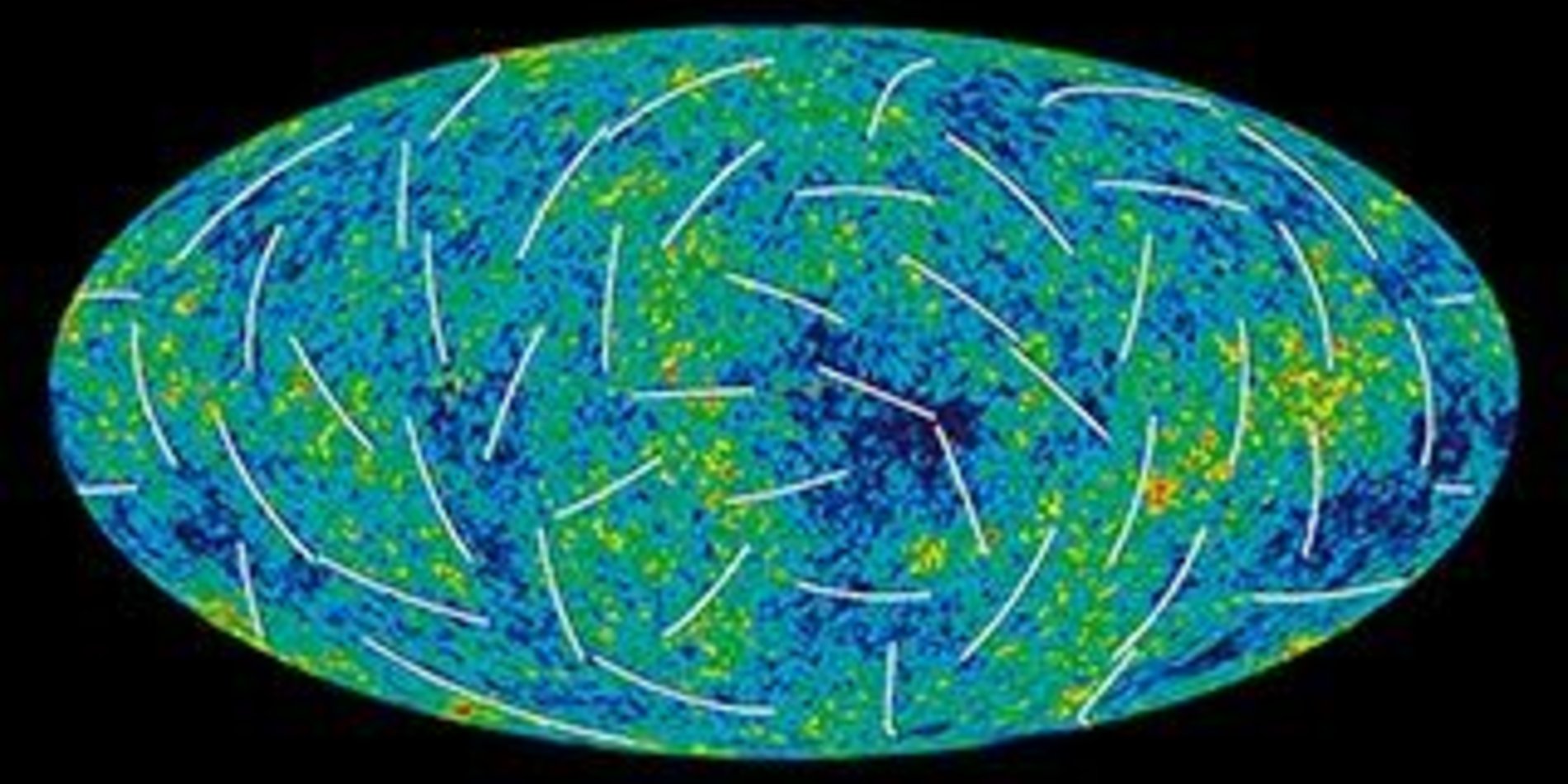

After traveling for more than 13 billion years, these photons have become redshifted into the microwave part of the spectrum with a wavelength of around one millimeter (which translates to a frequency around 300 GHz in the radio band). Their signal displays tiny anisotropies, or variations, related to fluctuations present in the density of matter before decoupling.

The typical size of these anisotropies has been easily measured by current CMB experiments and leads to another value for H0, the latest of which comes from data furnished by the Planck spacecraft, resulting in a value much lower than that derived from SN1a: H0 = 67.8 +/- 0.8 km/ s/Mpc. Accounting for the error bars, there is a 3.6 sigma discrepancy between the H0 value measured by this method and that extracted from the SNIa method described in the previous section. The reason for this discrepancy is currently an enigma.

Cracks in the Model, Part III: Will the real H0 please stand up?

This brings us back to possible cracks in the LCDM model—in theory, the discrepancy between different measurements of H0 could be pointing to a need to extend some of the model’s parameters (for example, through quintessence models or the existence of a exotic new type of particle called a sterile neutrino) or even modify general relativity (for the curious, more details on these are available in a very comprehensive review by Philip Bull, et al., 2016).

Given the fact that this discrepancy arises when early and late Universe probes are combined, one possibility is that the Universe expanded differently at early and late epochs. This would be incredibly Universe-shaking to cosmologists, if true. But to settle the matter we need to fully understand the systematic errors that can cause us to under- or over-estimate H0, and further, how we can continue to reduce these error values.

The discussion has been very lively over the last year. In the fall of 2018, an interesting paper exchange in the arXiv happened between two supernovae groups led by Riess and Shank (see "Related reading," below). Future surveys will certainly shed light as to whether this discrepancy reflects some underlying cosmological issue, or whether the resolution lies in the systematics.

Enter the newest kid on the block: Simons Observatory

Meanwhile, researchers continue to build more sensitive instruments in an effort to hone in on the true value of H0.

The CMB is a particular focus of KIPAC. Many of our members have very important roles in experiments like the BICEP Array at the South Pole and are instrumental in several upcoming ground-based CMB surveys—including the Simons Observatory (SO). For my part, during my graduate studies I joined the POLARBEAR Collaboration (whose primary telescope is shown below in Fig 2) and contributed to the analysis effort for the first three seasons of data that were collected. Three years ago, I joined the Simons Observatory collaboration.

The SO is an up-and-coming array of instruments comprising one 6m telescope and three 42cm telescopes that will observe at several different microwave frequencies to both capture the CMB peak signal and constrain polarized foreground contamination from galactic synchrotron and dust emissions at lower and higher frequencies.

SO will be located in the Atacama desert, an extremely dry site at about 17,000-foot elevation on a high desert plateau in northern Chile at the same location as POLARBEAR has been running. Observations are expected to start in the early 2020s.

In the figure below, we see SO performance forecasts on H0 constraints.

The total uncertainty expected from SO is about a factor of two better than the Planck estimates and five times better than the estimates from SNIa. In fact, the sensitivity in polarization will be high enough that SO data alone can be use to estimate H0 by cross-checking the three observables contained in the CMB information—temperature anisotropy, polarization, and the cross-correlation between them. (See Fig 3.) This will provide a further check for internal consistency as well as robustness against inherent systematic errors in each type of observation.

Reaching back even farther - to within the first second of the Universe's existence

The CMB fluctuations are polarized, and since the year 2000, when polarization anisotropies were first detected, CMB surveys have been improving the upper limits on the amplitude of a particular polarization pattern called the B-modes at about degree-size angular scales. This polarization might be related to a stochastic sea of gravitational waves undetectable by current facilities—or even planned future ones such as LIGO Voyager, or LISA—emitted during the inflationary era in the first instants following the Universe’s birth—within the very first second of its existence. The B-mode amplitude is parametrized by the tensor-to-scalar ratio parameter, r, which characterizes the theory beyond the simplest LCDM model. The detection of primordial B-modes will allow us to discard several inflationary models, as can be seen in Fig 4 below.

Back to the future for the CMB

The future for CMB experiments is extremely suspenseful for all those who would like to understand the resolution of the H0 discrepancy (along with several other cosmological mysteries). All the current ground-based telescopes located in Chile and South Pole are in the process of sharply increasing their sensitivity so that we will in the future be able to reach much further in our understanding of the Universe. Stay tuned!

Related reading

- SPT-3G deployment: Going to the ends of the Earth to capture pictures of the infant universe (2017)

- Latest measure of cosmic expansion hints that universe is growing faster than expected (2017)

- The Riess and Shank papers (all from October 2018)

- GAIA Cepheid parallaxes and 'Local Hole' relieve H0 tension

- Seven Problems with the Claims Related to the Hubble Tension in arXiv:1810.02595

- H0 Tension: Response to Riess et al arXiv:1810.03526

Related Research Areas

Cosmic Ecosystems

Cosmologists at KIPAC study the structure of the Universe from nearby galaxies and their satellites to the distribution of galaxies on the largest scales across the Universe.