Observing the Beginning of the Universe at the Bottom of the World

The South Pole boasts some of the most extreme living conditions on the planet: high altitude, an extremely dry atmosphere, bitter cold, and one sunrise and sunset per year. These conditions make sustaining life nearly impossible at the bottom of the world; however, they also make the South Pole a haven for cosmology research, and specifically for observing the microwave universe.

Just like the way microwaves from your microwave oven are absorbed by the water in your food, microwaves from space are absorbed by the water in the atmosphere. The dry, stable atmosphere of the South Pole lets us collect as many of these cosmic microwaves as possible. This is why, every southern-hemisphere (austral) summer, scientists from around the world travel to the South Pole to upgrade and maintain world-leading microwave observatories.

Why do we care about cosmic microwaves?

These South Pole telescopes aim to measure the oldest light in the Universe, also known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB). The very early Universe was an extremely hot, dense plasma of elementary particles. Photons continuously bounced off of these elementary particles, rendering the Universe opaque. After about 380,000 years this plasma cooled down enough that atoms could form, reducing the density of particles and allowing photons to travel without bouncing into anything. These photons are known as the CMB, which became imprinted with a picture of the distribution of particles at the moment they last scattered, making the CMB our best window into the early Universe.

Just after the beginning of the Universe, cosmologists believe that there was a period of extremely rapid expansion. This idea is known as the theory of inflation, and it can explain a lot of properties we observe today. While there is a treasure trove of information contained in the CMB, the BICEP collaboration—a global team of scientists from 8 universities and 3 US national labs—is most interested in measuring a signal of inflation that would be found in the CMB.

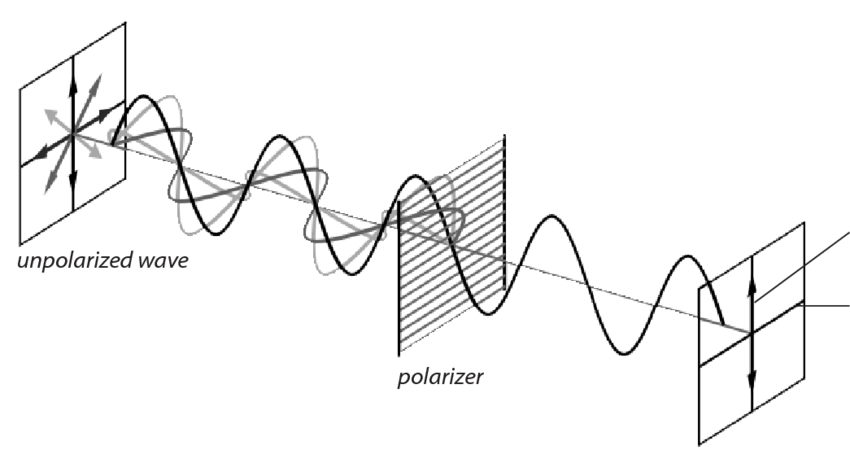

Light is an electromagnetic wave, meaning that it is composed of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. In unpolarized light, the direction of the electric field fluctuates randomly over time, while polarized light has oscillations of the electric field that are aligned in a specific direction. If inflation did occur, the violent expansion would have produced gravitational waves that would have imprinted themselves into the polarization of CMB photons. Measuring the effect of gravitational waves on the CMB polarization would provide compelling evidence for definitively determining if early-Universe inflation occurred.

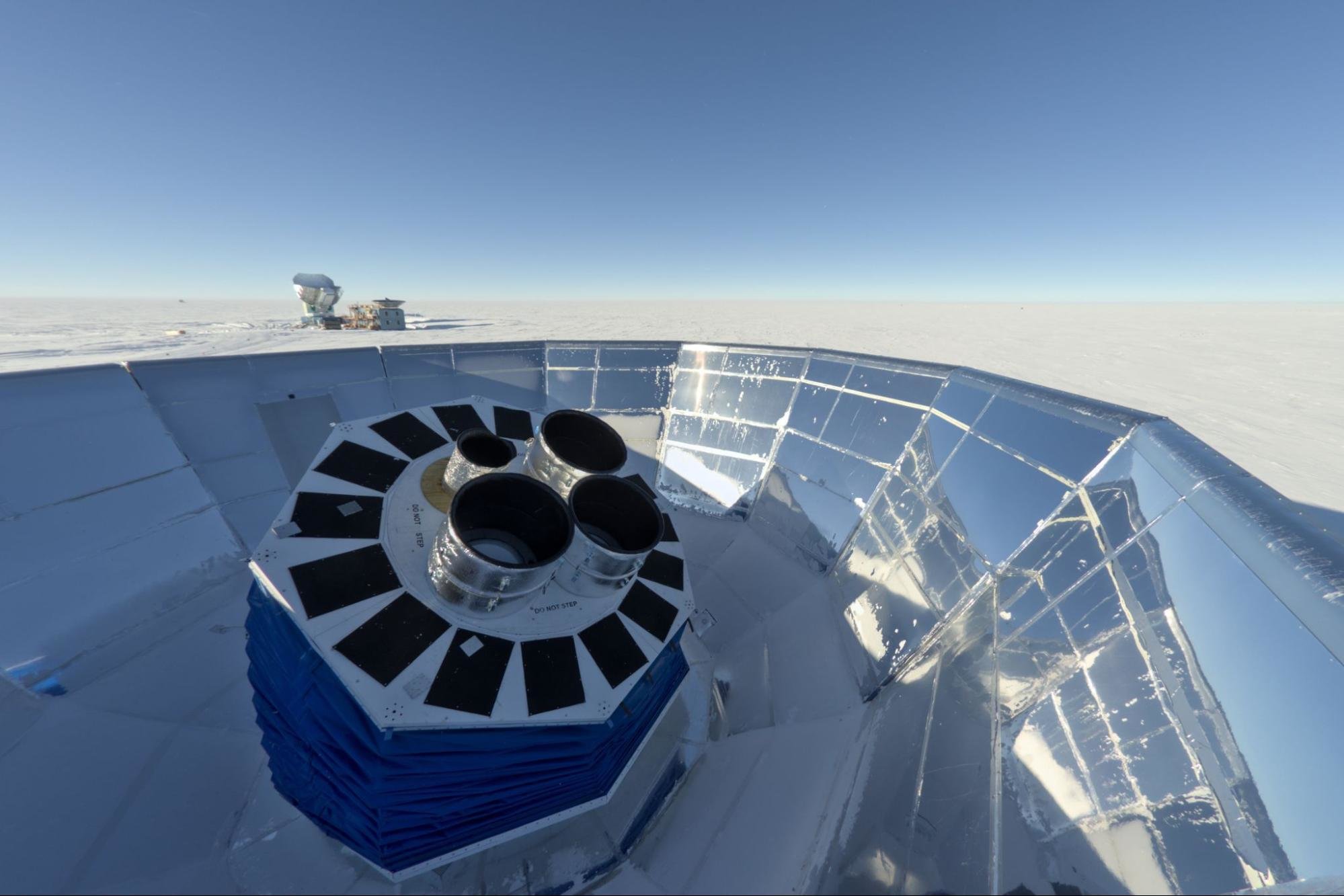

The BICEP Array Experiment

The CMB is at a temperature of around 3 Kelvin (K) (this is -270 C, or -454 F!), with tiny ~100 mK fluctuations. The BICEP Array experiment will feature four “receivers” (akin to cameras) that house superconducting detectors able to detect these tiny fluctuations (the insides of these cameras get as cold as 300 mK!). However, there are many other sources of microwaves in the Universe besides the CMB. These other sources of microwave emission, known as foregrounds because they exist between us and the CMB, contaminate our picture of the early Universe and its polarization. One such foreground is cosmic dust, the result of the accumulation of small, solid clumps of matter through the billions of years of the Universe’s evolution. This dust foreground is brightest towards the high end of the microwave spectrum (frequencies greater than ~200 GHz). During the 2024-25 austral summer, I traveled to the South Pole with an excellent team of BICEP scientists (including Stanford’s own Cheng Zhang and Yuka Nakato) to assemble, install, and commission the telescope’s high frequency camera, known as BA220/270. This camera is sensitive to light in two frequencies (220 and 270 GHz) and will give us a picture of cosmic dust, allowing us to more effectively remove the dust foreground from our data.

Life at the South Pole

While commissioning a brand new receiver is a lot of work, life at the South Pole Station presents its own comforts and challenges! The BICEP Array telescope is housed in the so-called dark sector where we remove sources like WiFi that emit the same kind of radiation that our telescopes can see. This means that twice every day we have to walk about a half mile from the station where we live to this dark sector in order to work on our telescope. Being outside can be incredibly cold, but luckily we are each given a big jacket, known as a “Big Red,” that keeps us insulated and warm. Inside the station, there are plenty of community-lead activities that keep us busy on our off days like dance classes in the gym, workout classes, and movie nights!

Edited by Toby Satterthwaite, Lori Ann White, and Josephine Wong

Related Research Areas

Related Research Areas