Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument

The Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) is the heart of a ground-based survey that will spend the first half of the next decade pinpointing the locations and spectra of up to 35 million galaxies and 2.4 million quasars across one-third of the night sky.

DESI observations will be used to create a 3D map of a huge volume of space that stretches more than 11 billion years into the past. For millions of objects, the map will reveal how fast the Universe was expanding at different times. Such accurate measurements of the expansion history over the past 11 billion years will help constrain possible models of dark energy.

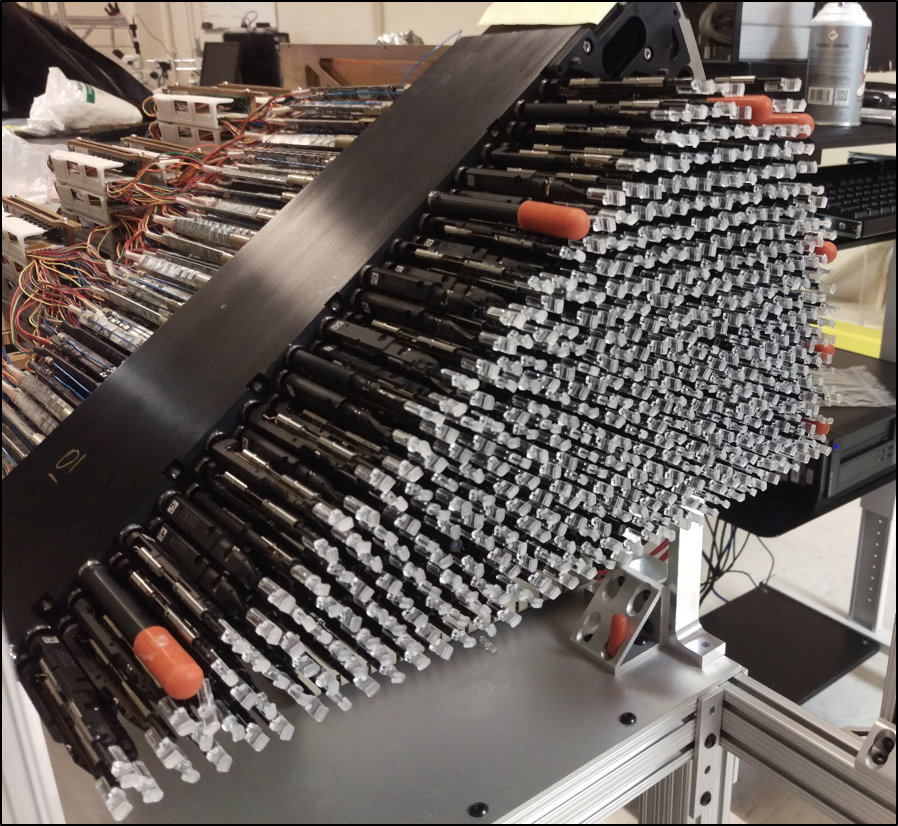

5000 eyes on the sky

DESI will collect that information from its perch on the four-meter Mayall Telescope on top of Kitt Peak. A meter-wide focal plane houses 5000 robot actuators adjusting 5000 optical fibers, each one of which can capture the light from a single galaxy or quasar and feed it to one of ten identical spectrographs.

DESI will focus on four different types of targets, each of which contributes different information about cosmic evolution:

Bright galaxies

Bright galaxies, or galaxies of magnitude 20 or below, are bright enough to observe when the moon is near full, and will provide a solid foundation for DESI's map. They extend back to about 4x109 light years and probe the recent Universe, when the accelerating expansion is strongest.

Luminous red galaxies

Luminous red galaxies (LRGs) are the most massive galaxies, composed largely of old stars. They stretch back to about 8x109 light years, but their red color makes them easy to select in imaging.

Emission line galaxies

DESI's largest sample will be of emission line galaxies (ELGs). These are fainter and more distant, but their vigorous star formation and hot young stars produce strong emissions in wavelengths detectable by DESI out to about 1010 light years).

Quasars

The furthest of DESI's targets in time and space are quasars, galaxies with extremely active central supermassive black holes. Quasars outshine the stars of their own galaxies, achieving luminosities that enable DESI to detect them out to about 1.2x1010 light years and beyond.

Quasar light is also partially absorbed by neutral hydrogen in massive gas clouds found in intergalactic space. This results in a spectral absorption pattern called the Lyman-alpha forest that's detectable by DESI, which means that each quasar spectrum not only reveals its location, but also a map of the intergalactic hydrogen along the line of sight.

Bonus: our own galaxy

Finally, DESI will observe stars in the Milky Way, adding to our understanding of the chemical abundances and gravitational dynamics of our home galaxy. This information will contribute to dark matter research.

DESI science

As the name suggests, DESI's primary mission is to help constrain dark energy, but the same maps will provide other opportunities to study cosmology and the physics of galaxies, quasars, and intergalactic gas.

Dark energy

DESI's maps will provide measurements for two important probes of dark energy: baryon acoustic oscillations (BAOs) and redshift space distortions (RSDs).

BAOs

BAOs are the detectable remnants of sound waves traveling through the primordial plasma that existed before the Universe cooled enough to let neutral matter form. These sound waves were shaped by density perturbations created in the first second of the Universe—density perturbations thought to furnish the seeds of all future cosmic structure.

But the effects of the sound waves can still be detected as a slight tendency for pairs of galaxies to be separated by the distance the waves traveled, which—owing to the expanding Universe—is about 500 million light-years today. When DESI's maps show this distinctive galaxy clustering, researchers already know how far apart the galaxies lie—500 million light-years. We can use it as a standard ruler to determine the scale of the Universe over a wide range of time periods with subpercent precision. From this information we can construct an expansion history of the Universe and follow the evolution of dark energy.

The redshift (reddening of light from a source due to it receding from a viewpoint location) of an individual galaxy within a cluster may be slightly affected by the gravitational pull of other galaxies within the cluster. This is the source of the second dark energy probe, RSDs. By measuring these smaller variations in redshift, researchers can measure the growth of large-scale structure which could also tell us the history of the Universe.

Beyond dark energy

The DESI maps will also contribute to measuring the mass of the neutrino, help researchers characterize the initial density perturbations in the extreme early Universe, and provide data for testing a wide range of extensions to the standard cosmological model.

Beyond cosmology, DESI will measure precise distances to millions of galaxies and quasars whose properties and demographics can then be better interpreted. DESI will produce the most detailed map yet of the nearby Universe, providing a firm foundation for studies of galaxy groups and clusters as well as of extreme phenomena within those galaxies. And DESI’s stellar spectroscopy will measure the dynamical state of the Milky Way halo and thick disk in great detail.

For more information about DESI, visit the official DESI website.

Related Research Areas

Related Research Areas

Cosmic Ecosystems

Cosmologists at KIPAC study the structure of the Universe from nearby galaxies and their satellites to the distribution of galaxies on the largest scales across the Universe.

Physics of the Universe

At KIPAC, we are working to understand the physics that shapes the origins, evolution and fate of the Universe.Related People

-

Postdoctoral Scholar

Postdoctoral Scholar -

Professor of Particle Physics and Astrophysics

Professor of Particle Physics and Astrophysics -

Physical Science Research Scientist

Physical Science Research Scientist -

Senior Scientist

Senior Scientist -

Ph.D. Student

Ph.D. Student -

Professor of Particle Physics and Astrophysics

Professor of Particle Physics and Astrophysics -

Lead Scientist

Lead Scientist -

Postdoctoral Scholar

Postdoctoral Scholar -

Staff Scientist

Staff Scientist -

Postdoctoral Scholar

Postdoctoral Scholar -

Director, Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), Humanities and Sciences Professor and Professor of Physics and of Particle Physics and Astrophysics

Director, Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC), Humanities and Sciences Professor and Professor of Physics and of Particle Physics and Astrophysics