Research projects

Main content start

Cosmic Microwave Background Surveys

-

Simons Observatory

Currently under construction in Chile’s Atacama Desert, the Simons Observatory (SO) is a next-generation observatory that will look for signs of cosmic inflation and answer fundamental questions about the origin of the Universe. -

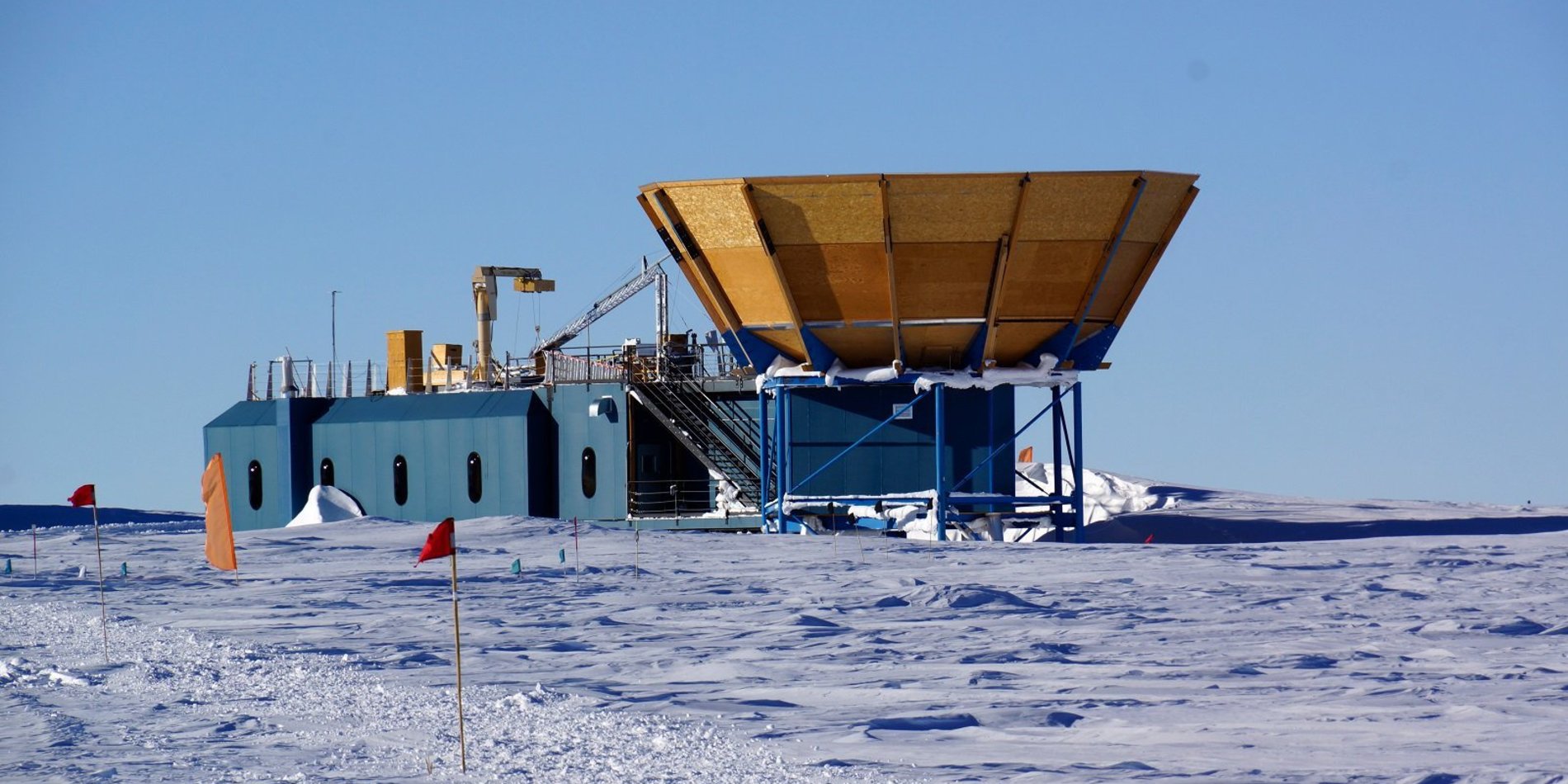

South Pole Observatory

The South Pole Observatory combines the BICEP Array and South Pole telescope

Dark Matter Experiments

-

Dark Matter Radio

The Dark Matter Radio, or DM Radio for short, is an experiment that detects dark matter like an AM radio. But unlike a radio it uses exquisitely sensitive superconducting devices. -

LUX-ZEPLIN

The LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment is searching for WIMP dark matter. -

Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search

Observations of galaxies, galaxy clusters, distant supernovae, and cosmic microwave background radiation tell us that about 85% of the matter in the universe is made up of one or more species of dark matter.

Data and Computation

-

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

At KIPAC, researchers are working to advance the frontiers of astronomy through the application of AI and machine learning, and simultaneously pushing the frontiers of AI/ML methods in pursuit of astrophysics discovery. -

Computational Astrophysics

KIPAC researchers tackle a wide range of computational challenges as part of a mission to bridge the theoretical and experimental physics communities. -

Scientific Data Visualization

KIPAC's visualization and data analysis facilities provide hardware and software solutions that help users at KIPAC and SLAC to analyze their large-scale scientific data sets.

Optical Surveys

-

Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument

DESI is the heart of a ground-based survey that will spend the first half of the next decade pinpointing the locations and spectra of up to 35 million galaxies and 2.4 million quasars across one-third of the night sky. -

Dark Energy Survey

The Dark Energy Survey (DES) is a large survey of distant galaxies that aims to unravel the mystery of cosmic acceleration. -

Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope

The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (formerly the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, or WFIRST) is a mission designed to study dark energy, the evolution of galaxies, and the populations of extrasolar planets. -

NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory's Legacy Survey of Space and Time

The Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) is a planned 10-year survey of the southern sky that will take place at the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory, located on the El Peñon peak of Cerro Pachón in northern Chile. -

Via

The Via Project is using the Milky Way galaxy as a laboratory to answer fundamental questions about the nature of the universe. Via will conduct an all-sky survey of stars using the 6.5-meter MMT (Arizona) and Magellan (Chile) telescopes.

Solar

-

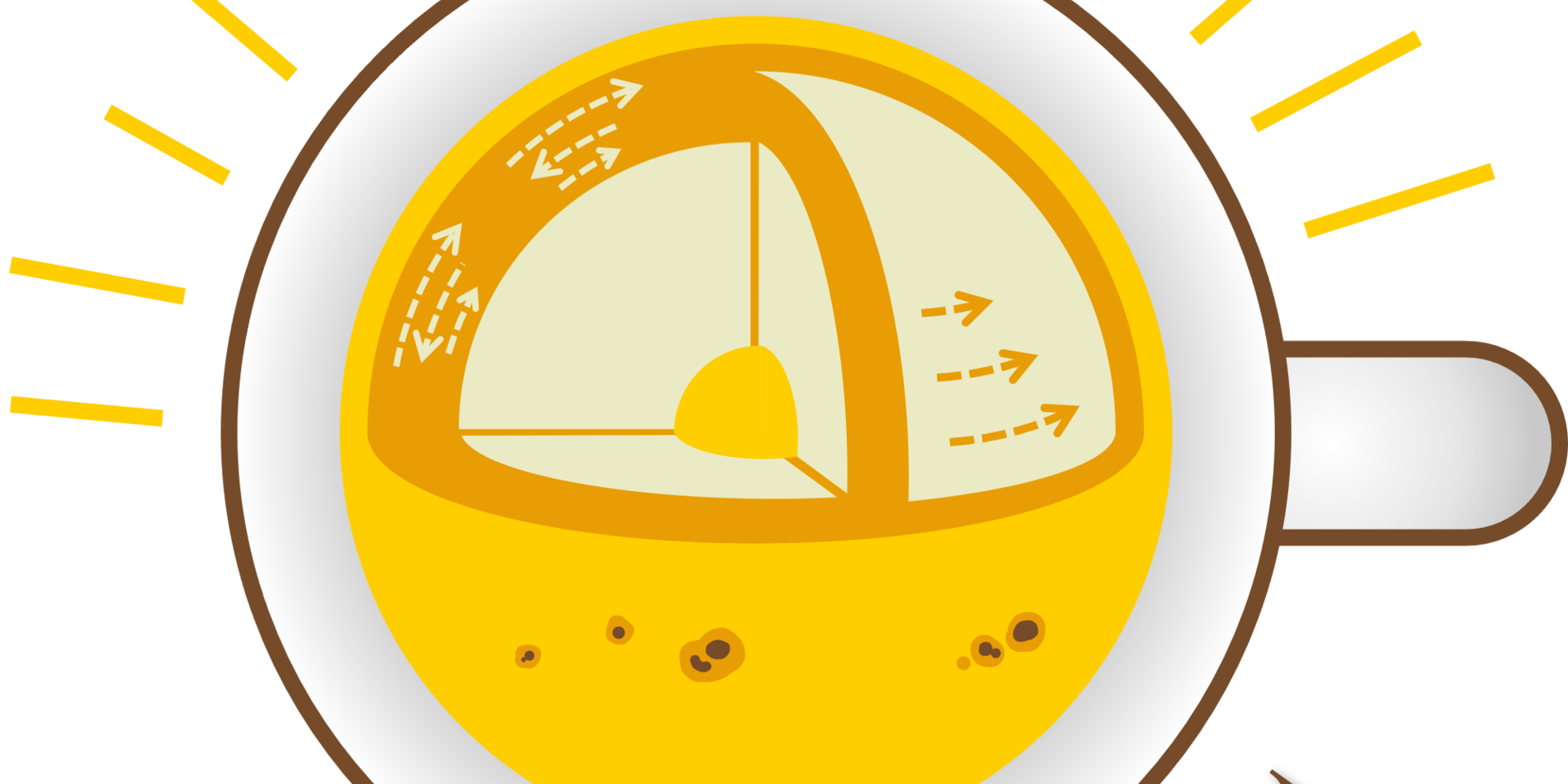

COFFIES DRIVE Science Center

COFFIES is a NASA-funded Phase II DRIVE Science Center with the goal of solving some of the most difficult mysteries hidden in the deep interior of our Sun.

X-Ray and Gamma Ray Telescopes

-

Athena

Athena, the Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics, is the next flagship X-ray observatory, planned for launch by the European Space Agency (ESA) in the early 2030s with a significant contribution from NASA. -

Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (FGST or Fermi) is a space-based observatory used to perform gamma-ray astronomy observations from low-Earth orbit. -

Imaging X-ray Polarization Explorer

The Imaging X-ray Polarization Explorer (IXPE), scheduled to launch in 2021, will be the first satellite dedicated to measuring the polarization of X-rays emitted by astrophysical objects in the 1-10keV band. -

The Advanced X-Ray Imaging Satellite (AXIS)

The Advanced X-Ray Imaging Satellite (AXIS) is a next-generation, high-spatial-resolution X-ray observatory designed to transform our understanding of the universe.